Ecological footprint of the richest: Methodology

Introduction

This methodology is part of the research on the inequality of overconsumption which attempts to quantify the full ecological footprint of the richest people in different countries around the world. Read a summary of the working paper published by the Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University (read the full working paper).

This methodology is part of the research on the inequality of overconsumption which attempts to quantify the full ecological footprint of the richest people in different countries around the world. Read a summary of the working paper published by the Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University (read the full working paper).

It is very difficult to obtain information on the environmental impact of the richest so the objective here is to try and observe trends based on the data that is available whilst knowing this does not give a complete picture of their ecological footprint. The exercise below is just one way of approaching this question. As this is an evolving research area with large gaps in data the aim of this exercise is to stimulate collaboration and innovative ideas on measuring the ecological footprint of HNWIs. To submit data see the country profiles for the United States, Japan, China, United Kingdom and France.

As there is no data or research available on the ecological footprint of the richest the focus here is on High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) in the countries where they are concentrated: the United States, Japan, China, United Kingdom and France.

Identifying the richest people

According to the latest World Wealth Report in 2014 there were around 14.6 million High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) defined as “having a minimum of US$1 million in investable wealth, excluding primary residence, collectibles, consumables, and consumer durables”. The majority of HNWI lived in the United States (4.3 million), Japan (2.4 million), Germany (1.1 million), China (890,000), United Kingdom (UK) (550,000) and France (494,000) (World Wealth Report, 2015). Together these make up nearly 10 million people.

Although this research focuses on HNWI another way to try and quantify the environmental impact of the richest people in the world would be to use the 2014 billionaire census which estimates there are 2,325 billionaires with a combined worth of $7.3 trillion (12% increase compared with 2013). Billionaires are “defined as those individuals with a net worth of US$1 billion or above”. The majority of billionaires live in the US (571), China (190), UK (130), Germany (123), Russia (114), India (100), Switzerland (86) and Hong Kong (82) (Wealth-X, 2014; Forbes, 2015). As would be expected the location of billionaires broadly correlates with the list of countries where HNWI live although it should be kept in mind that billionaires tend to value certain cities, such as New York and London, above particular countries.

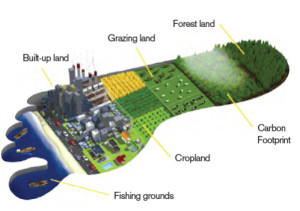

Defining the ecological footprint

This research uses the ecological footprint as a reference point to discuss the overconsumption by the richest people in society. The Global Footprint Network methodology explains that the “ecological footprint of a person is calculated by considering all of the biological materials consumed and all of the carbon dioxide emissions generated by that person in a given year.” This includes a person’s consumption of products from fisheries, cropland, grazing land, forests (wood and capture of carbon dioxide), and also use of urban land (Global Footprint Network, 2015). There are limitations in using this uniform approach across different areas and also due to insufficient data, which are acknowledged by the creators of the ecological footprint methodology (BBC, 2015).

Strengths and weakness of using household expenditure surveys

To try to get an indication of the size of the ecological footprint of the richest household expenditure surveys are used because of their relative ease in identifying the consumption patterns of different income groups. While this is not ideal, because it means broadening the scope to the richest 10% of the population (by income) instead of just HNWIs, it is a starting point. A common way of acquiring household expenditure data are via surveys that use a representative sample.

The assumption here is that because the richest spend more than each of the income deciles below them, then this will translate into the richest 10% having a larger ecological footprint. This seems a reasonable assumption given that ‘empirical analysis has shown a higher per-capita use of environmental resources by high income groups, while poorer segments of society, due to their lower levels of consumption, cause less harm to the environment’ (Laurent, 2014; Pye et al., 2008). An OECD review in 2008 noted ‘most studies conclude that consumption behaviour-related environmental pressure increases with household income. This can be observed in relation to waste, recycling, transportation choices and domestic use of energy and water’ (Berthe and Elie, 2015).

Limitations include:

However, household expenditure surveys only give an insight in to the ecological footprint of the richest 10%. The amount of money spent might not accurately reflect the ecological footprint because either the market price of goods and services are:

- ‘Too low’ e.g. negative externalities such as emissions of greenhouse gases used to make or transport the product are not included in in its price.

- ‘Too high’ e.g. organic food which often has a low (or beneficial) impact on the environment may be more expensive than mass produced food produced by industrial agriculture (Nierenberg, 2015).

When attempting to track the environmental impact of the richest it is important to keep in mind that the richest can afford more expensive things such as organic food and eco-friendly goods that may cost more but are better for the environment (Berthe and Elie, 2015). In addition research shows that some products with the same carbon footprint are sold at different prices (Gough et al,. 2011)) and that the richest tend to pay higher prices (Girod and De Haan, 2010). In these cases expenditure would not be an accurate way to measure the actual volume of goods and services purchased, and therefore not a good way to determine the ecological footprint.

Other limitations include:

- Household expenditure surveys are based on samples

- There is a risk data is not accurate because it is difficult to get information on the spending of the richest (Bernasek, 2006).

- Grouping households together by income hides the diversity of consumption levels within an income level (Capstick et al,. 2015).

Choice of indicators of the ecological footprint of the richest

As well as looking at total expenditure two key indicators are private transport and meat:

Private transport and food (along with domestic energy use) have been identified as the main sources of individuals’ environmental impact in developed countries (Peattie and Peattie, 2009). In 2012 total transport emissions (including aviation) made up around 20% of total EU emissions (EC, 2015) while in the US it was nearly a third (EPA, 2015). Meanwhile the production, transportation and packaging of meat has a huge ecological footprint with livestock estimated to be associated with 14.5% of annual global emissions (FAO, 2013).

They represent examples of direct (fuel used in private vehicles) and indirect (meat) greenhouse gas emissions. It is important to cover both types of indicator because there are numerous studies that show the majority of emissions in developed countries are often indirect, for example from food, consumer electronics, clothing and recreation (Capstick et al,. 2015; Büchs and Schnepf, 2013; Druckman and Jackson, 2008).

Leave a Reply